Written by Elaine Mead -

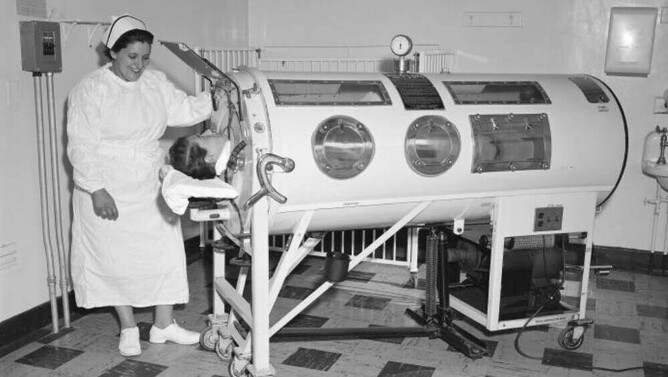

When I was six years old, my grandmother was rushed to Auckland Hospital emergency one evening and the family gathered, as the outcome was grim. At that age, you don’t appreciate the gravity of such a situation, and sitting and waiting is boring. So, my cousin and I explored the hospital corridors. I discovered a large, dimly lit room where someone lay in a big box, with just their head sticking out. The regular thump and suck of air provided an eerie background and added to a sense of isolation and mystery. Whilst I was curious, I was also pretty certain we shouldn’t be there and we scarpered back to family safety.

If you recognise the photos or the description above of my first (and only) experience of seeing an ‘iron lung’, you’ll know I’m talking about polio (poliomyelitis). Polio, once known as ‘infantile paralysis’, is a highly infectious viral disease affecting the spinal cord and nervous system, which is spread person to person through contaminated food or water. It is thought to have been around from the time of the Ancient Egyptians, where carvings show people with withered limbs and children walking with canes at a young age. The 20th century saw the rise of polio epidemics and New Zealand experienced outbreaks from 1916 until 1961, with around 10,000 reported cases over this period.

That spooky hospital encounter has not been my only experience with the after effects of polio. My great-uncle contracted polio as a young man living in the East End of London in the 1920s, which left his left leg withered and weak. The third youngest of seven, he was house-bound, unable to get about with other young lads of his age but his determination saw him create a cart which provided mobility and a vehicle for selling fruit and vegetables. Amazingly, he reached the fine age of 86 but wore callipers all his life and spent his last years in a wheelchair.

In New Zealand, the highest number of deaths in one year occurred in 1925, when 173 people died but the polio epidemic that gripped the country for more than two years after World War II was the most persistent outbreak. The first case was in Auckland in late 1947 and numbers increased rapidly in the city. It then spread to Waikato and Taranaki and throughout the North Island during the summer, peaking in Wellington at the start of winter 1948. By the end of the year it had dispersed widely in the South Island.

Polio was a much-feared disease. It mainly affected children and young adults, and how it was communicated between people was not well understood. It struck randomly, the symptoms sometimes didn’t appear for 7 – 10 days and people could be carriers with no signs of symptoms. Worst of all, there was, and still is, no cure.

People I have spoken with through my work as a personal historian remember schools, swimming pools and public facilities being closed. Children were prohibited from staying in motor camps, attending Sunday schools or inter-island travel and they were confined to heavily disinfected homes in an attempt to control the spread of the virus. In Auckland, there were stern warnings against swimming at local beaches and hospital patients in polio wards were not allowed any visitors, not even their parents.

Whilst some remember this as a period of ‘extended holiday’, pupils were expected to complete lessons by correspondence and listen to school broadcasts on radio. Once they returned to school the impact of the epidemic was evident in those with wasted limbs, wearing callipers or the absence of friends and fellow pupils who did not return.

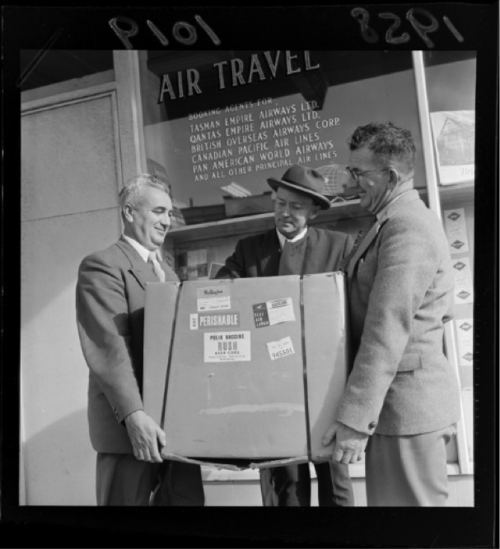

Jonas Salk’s vaccine injection was licensed in 1955 and, in a magnanimous gesture, never patented by its developer. The arrival in New Zealand of the first vaccine in 1958 was a major event, with people queueing at the airport, hoping to get a vial. This was followed in 1961 by the cheaper and more easily administered oral vaccine developed by Albert Sabin. A mass immunisation campaign in New Zealand, using the Sabin oral vaccine, achieved high population coverage and eliminated the polio virus from this country.

The last case of polio virus in New Zealand was in 1977, so many people from Generation X onwards have no knowledge of polio, the impact it had on society or its lingering after-effects. My understanding and experiences with polio continue through my Rotary membership. Rotary International’s efforts led to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which aims to eradicate the disease by providing polio vaccines to every child globally, ensuring a polio-free world for future generations. Work started in 1988, when there were an estimated 350,000 cases of polio in 125 countries. Today there are approximately 42 cases in two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan, but there is still a long way to go. A country has to be free of polio virus cases for three years before the World Health Organisation declares it polio-free.

For the ‘forgotten’ survivors from pre-vaccine epidemics, many years after their original infection, they started reporting new symptoms and in the 1980s the condition of Post-Polio Syndrome was identified. There is a small and ageing group of New Zealand polio survivors whose symptoms of muscle pain and weakness, fatigue, joint pain and sleeping and breathing difficulties are the toll of the body managing for many years with previous damage.

All of these people have stories and memories to share of an important period in New Zealand history. Their resilience and determination to succeed despite circumstances, and their direct involvement with a time of miraculous advances in medical approaches, equipment and treatment is worth capturing.

For more information

polio.org.nz

www.endpolio.org

polioeradication.org